Before we get into how to control oversteer, let’s make sure we are all on the same page on what it is. A great friend and racecar driver, who shall remain unnamed, loved to use the following quote to explain the difference between the two like this:

“Understeer is when you turn in, and the car goes straight, and you hit the barriers with the front of the car. Oversteer is when you turn in, and the rear of the car overtakes the front, and you hit the barriers with the rear of the car.”

I don’t think his drivers ever forgot the difference between the two after that…

What Are The Types Of Oversteer?

A key factor here is to understand that there isn’t just one kind of oversteer. There are many scenarios where the rear can overtake the front, all with different causes. The following are the two main types of oversteer race car drivers experience:

- Trailing Throttle Oversteer (Snap Oversteer or Lift Off Oversteer)

- Power Down Oversteer (Corner Exit Oversteer)

Snap oversteer is the oversteer racecar drivers tend to feel just after turn in on corner entry. This is the corner that scares most drivers. In fact, we see it scare enough of the drivers we coach that they form a bad habit of picking up initial throttle just after turn in to avoid it at all costs.

There are a few issues with this, one of which is that it will lead to drivers experiencing the second form of understeer far more often!

Snap Oversteer

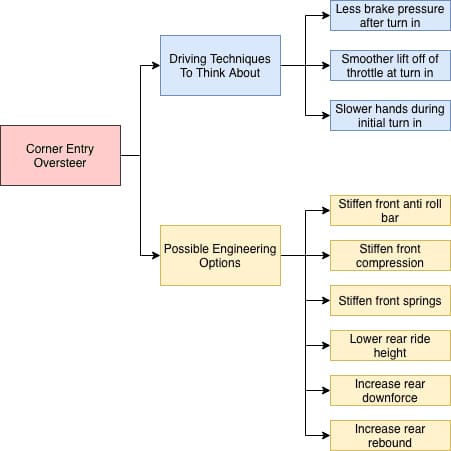

It is difficult to write an article that sums up every possible reason for oversteer on corner entries because there isn’t one common cause. Below are just a few common possibilities that can cause corner entry oversteer:

- Too much entry speed

- Too hard on the brakes after turn in

- Abrupt lift off of throttle after turn in

- Brake Bias too far to the rear

- Too high of rear tire pressure

- Way too low of rear tire pressure

- Not enough rear downforce compared to front downforce the car has

- Not enough rebound in the rear shocks

There are a lot more possibilities than that, but from my experience, there are some of the more common occurrences. I will break down a few of these in more depth now.

Here is a great video on learning how to drive a car at its limit - Finding The Limit Of Our Car

Too Hard On The Brakes After Turn In

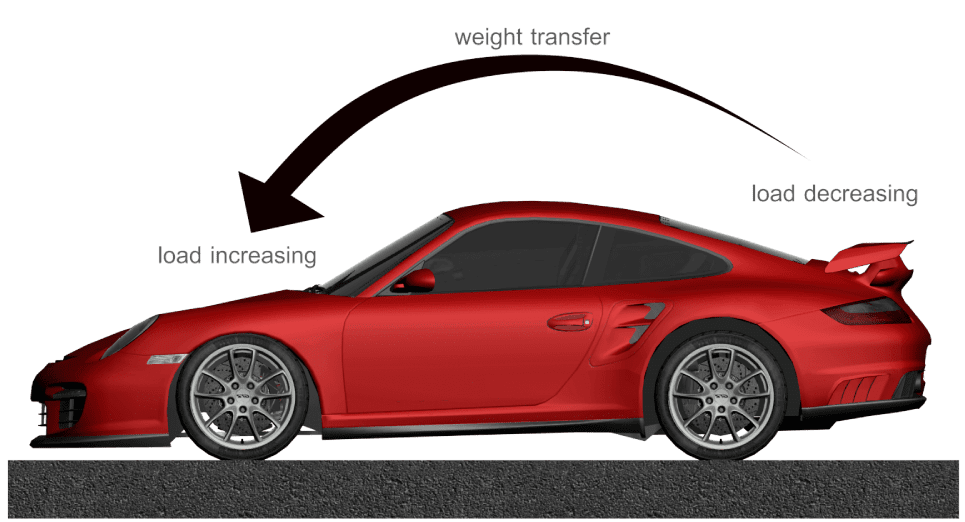

Too much pressure on the brakes after turn in can lead to oversteer because of a concept called weight transfer. Here is a fantastic in-depth article on this:

What Is Trail Braking & Why Is It Fast?

In almost every corner we want at least some brakes after turn in, but finding the balance of too little brakes compared with too much brake pressure is one of the hardest concepts for racecar drivers to find.

Too little brake pressure? Well, you are going to miss that apex because the car doesn’t want to turn.

Too much brake pressure? You are hitting that barrier with the back of your car.

The thing we need to understand first is that not all oversteer is evil. When we talk about oversteer it is normally in a negative connotation. But, we often to refer to oversteer with another word when it is a good thing. That word? Rotation.

It is very common to hear a driver in discussion with their engineer saying, “I just don’t have enough rotation on entry.” The driver here is essentially asking the engineer to let the car oversteer more.

Balancing The Car On The Brakes

So, now that we know oversteer isn’t all bad how do we figure out how to balance the car on the brakes? This is where we like to teach our drivers to make “intelligent mistakes.” Yes, you heard us right… We actually want to see the occasional mistake, but the keyword there is intelligent.

No driver has ever found the limit of the car without going over it. The key for amateur racing car drivers and even pro racing car drivers is to be able to find a way to experiment with the limit in the lowest risk way. Racing is inherently risky, but if we can be smart about the risks we take we can make great strides as drivers while keeping risks as low as possible.

Want to know how professional drivers deal with oversteer? This article and video are a must see!

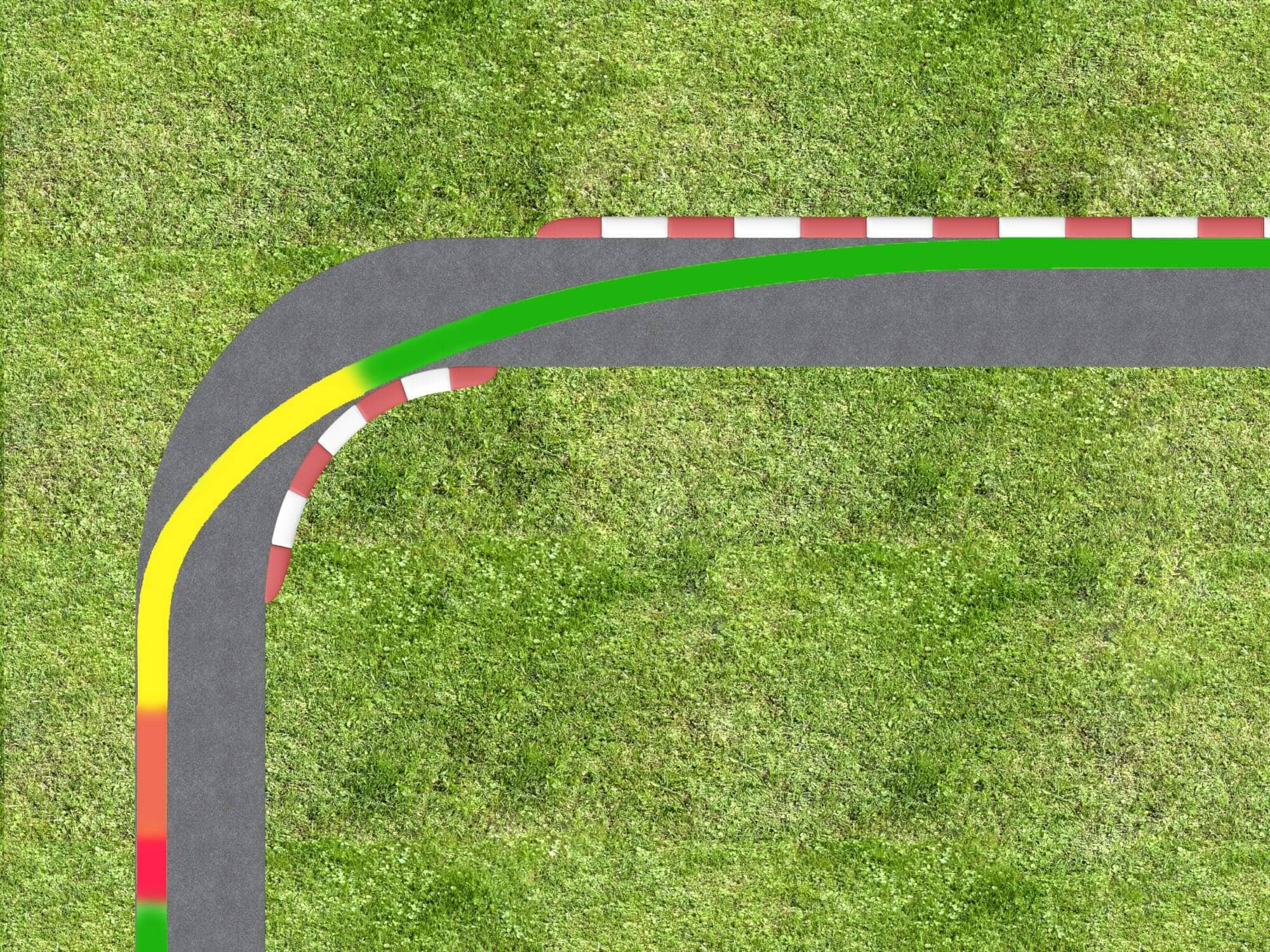

So, what we like our drivers to do is before a track day or race weekend take a second to visualize the track. Pick out a corner with a nice amount of runoff room and one that is not the fastest corner on the track. For this exercise, we will use Sebring International Raceway since a lot of us are familiar with this race track.

A good example of a “low risk” corner to experiment with:

Turn 7 - Great run-off room. If you are in too deep or have too much brakes on still at initial turn in the driver can open their hands and just go straight.

A bad example of a “low risk” corner to experiment with:

Turn 17 - This is one of the most difficult and high-risk corners of any corner on any track. We like to teach our drivers to eventually progress to experimenting on these corners, but we must first practice and perfect the lower risk ones first.

### Now that we have the corner we are going to focus practicing trail braking on. How do we do it?

My goals at Turn 7 are the following:

- No throttle until I can start to unwind the steering wheel

- Braking all the way down until the apex point

- Just the right amount of rotation to allow my throttle and initial unwind of the steering wheel to come right at the apex.

This diagram shows our trail braking objective. The red is threshold braking and we see it trail off to the light yellow before the turn in even starts. We keep that very light braking all the way down to the apex.\[/caption\]

Once we have figured out the general area we know we want to turn in and apex the experiment starts. The first step of this process is to work up slowly to the limit. We don’t want to work on braking deep first, no that is the last thing we do.

Finding a ballpark decent initial brake marker. Be consistent with your brake marker and initial brake pressure. We want to focus on the back end of the braking zone. As we work on trail braking we want drivers to think about braking for a longer period of time but with lighter pressure.

Get off of threshold brake pressure earlier, and then extend the back end of the braking zone. Once we get to the point where we are carrying the brakes all the way down to the apex, we want to **slowly** work up our initial brake marker.

As we work on edging up to the limit occasionally the driver will have slightly too much brake pressure on at turn in and that snap oversteer will show its face. If done slowly and correctly it won’t be a full on spin, instead, the rear will just have a little bit too much slide as we carve down to the apex.

Once we get to that point we just back up our initial brake zone slightly and work on having slightly less brake pressure at turn in. Going back and forth in this area is where we want our drivers experimenting. The more time they can experiment here the smaller adjustments they will be able to make and they will learn how to keep the car closer to the limit.

Remember trail braking ultimately isn’t about having a lot of brake pressure on all the way down to the apex. It should feel like your big toe is just resting on the brake pedal!

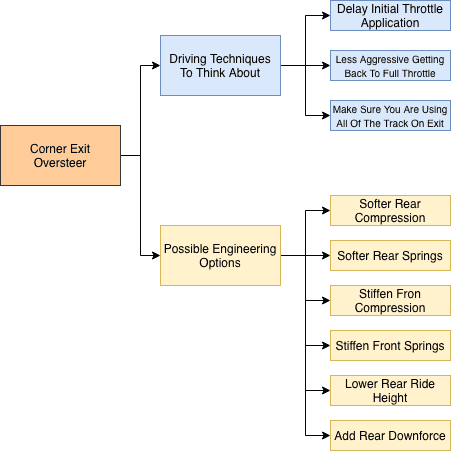

Power Down Oversteer

When speaking with engineers you will hear a driver speaking about a lack of traction. When they are talking about this they are letting the engineer know they have power down oversteer. Again there can be many causes of this, some of the main examples are:

1. The driver has too much steering wheel input as they hit the throttle aggressively

2. Too high of rear sprint rates, or rear shock compression

3. Not enough rear camber

4. Rear tire pressures too high

5. Tires are at the end of their life in terms of tire wear

The main area we want to focus on here is the first scenario. This is an area our racecar coaches focus on heavily with our drivers.

Remember in the first section we mentioned how trying to control oversteer on entry by getting to throttle can lead to an issue on exit? Well, the common thing we see is that by getting to throttle before the apex we take the weight off the front end and induce an understeer.

Once we have started the understeer it is nearly impossible to adjust out of it. We have to delay our full throttle point until we are all the way out at the exit curb where we can finally open our hands. This is due to that lack of rotation.

What we tend to see though is that drivers who do this get impatient and try to get back to significant throttle while they have a lot of steering input still in the car. Here the driver is binding up the car, the fronts are sliding over the track and the rears are fighting for traction. We are putting a ton of load in the outside rear tire, and quite often more load than it can handle. If the driver is asking the car for 60% of its total grip available to keep turning and then jams on the throttle and asks for 60% of the cars total grip available to go to traction we are going to see a massive snap on exit.

That is why we are so focused on where drivers pick up the initial throttle application. It goes back to the old string theory for drivers. If you aren’t familiar with that here is a great article by Indy Car driver Alex Lloyd:

To sum up this article below are two charts that break down what to think about if you are experiencing oversteer in terms of driver inputs or potential setup issues.

To help reduce your corner exit oversteer here is a very helpful article on video.